We’d like to remind Forumites to please avoid political debate on the Forum.

This is to keep it a safe and useful space for MoneySaving discussions. Threads that are – or become – political in nature may be removed in line with the Forum’s rules. Thank you for your understanding.

FTSE tracker

Comments

-

itwasntme001 said:Another_Saver said:

For convenience let's use year end 2009 to year-end 2019. This is far too short a time period to infer anything from.Steve182 said:

Last decade the difference has been massively in favour of S & P 500TBC15 said:

So what's the relative performance over say 10yrs?Another_Saver said:

Rather that than the S&P 500 full of dot com valuation consumer electronics and media companies, and healthcare companies that won't be around when the US inevitably switches to public healthcare.TBC15 said:The FTSE 100 is a Jurassic index, to be avoided at all costs.

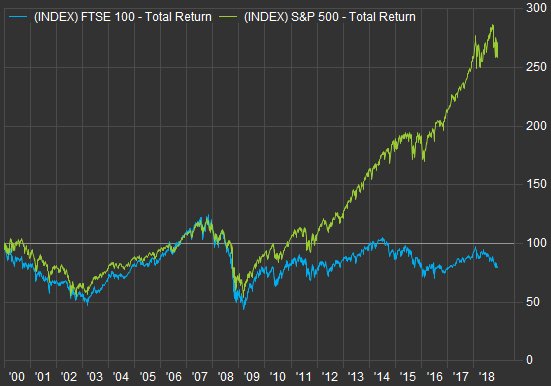

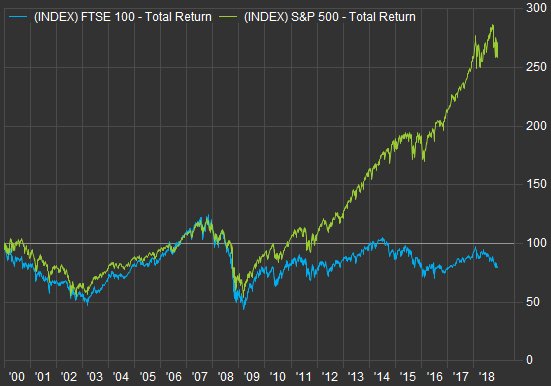

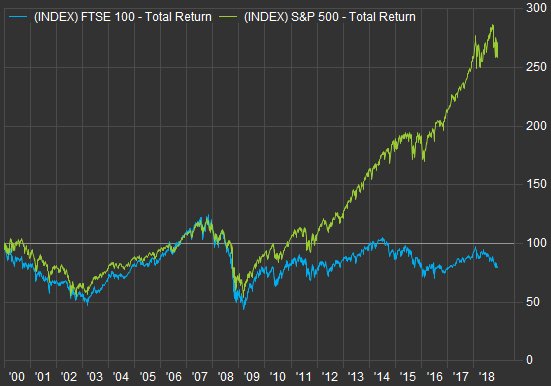

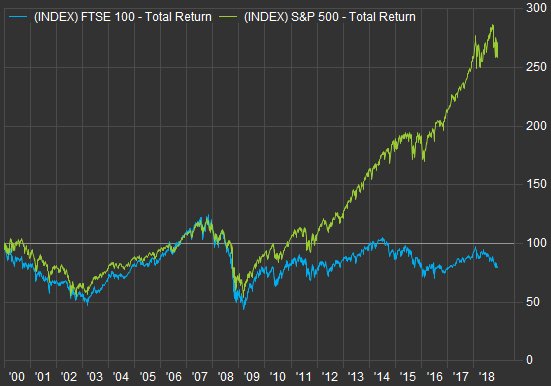

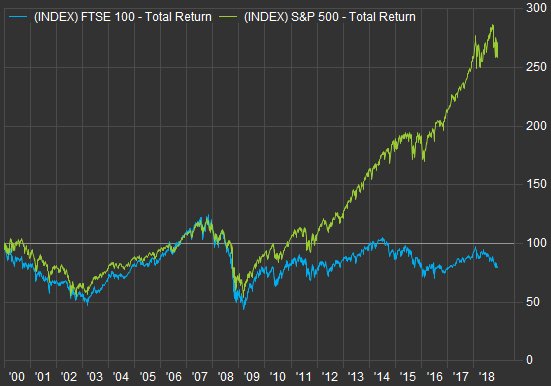

This is to 2018. You will find something more recent if you persevere on Google I'm sure. The trend has continued in the same direction since then, but that's no indication of what will happen next... The S&P returned 13.3%, the FTSE 100 7.39%, hardly a bad run, just less good. All figures are annualised.

The S&P returned 13.3%, the FTSE 100 7.39%, hardly a bad run, just less good. All figures are annualised.

The gap is 5.50%

The FTSE's PE fell from 17.78 to 16.45, -.78% pa

The S&P's PE rose from 20.7 to 24.88 +1.86% pa

So 2.66% of the gap is explained by relative speculation or rerating, leaving 2.77% explained by additional earnings growth in the US. Both countries inflation rates and corporate profits/GDP ratios were comparable and during this period the US experienced a significant corporate tax cut. The 2000s had also been a worse decade for US earnings than the UK, so a reversion to the mean was to be expected.

I don't see a trend, I see volatility, opportunity and value.

Edit: this isn't just the UK, the US has outperformed just about everything except bitcoin and Tesla in the last decade and year to date.This is a really good post and wish there was more of this sort of analysis on here. The US markets have benefited from monopolistic powers in tech (further exacerbated by their immense global reach) with an economic backdrop of disinflation (which has so far kept long term interest rates very low thereby boosting valuations).When we do get inflation returning, if it is in the context of reflationary economic conditions, a FTSE100 tracker should start to outperform the US markets.itwasntme001 said:Another_Saver said:

Everyone has always said that since the Acts of Union. Declinist nostalgic moaning isn't new, it's our oldest tradition. And the things you bemoan were only possible because of the empire (also known as stealing other peoples' countries for your own economic advantage), it's a structural change not an economic one.Steve182 said:

I disagree,Another_Saver said:

For convenience let's use year end 2009 to year-end 2019. This is far too short a time period to infer anything from.Steve182 said:

Last decade the difference has been massively in favour of S & P 500TBC15 said:

So what's the relative performance over say 10yrs?Another_Saver said:

Rather that than the S&P 500 full of dot com valuation consumer electronics and media companies, and healthcare companies that won't be around when the US inevitably switches to public healthcare.TBC15 said:The FTSE 100 is a Jurassic index, to be avoided at all costs.

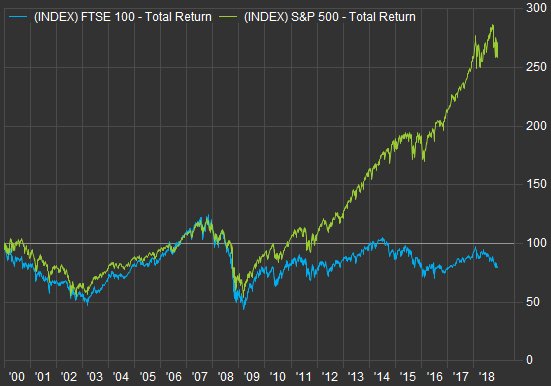

This is to 2018. You will find something more recent if you persevere on Google I'm sure. The trend has continued in the same direction since then, but that's no indication of what will happen next... The S&P returned 13.3%, the FTSE 100 7.39%, hardly a bad run, just less good. All figures are annualised.

The S&P returned 13.3%, the FTSE 100 7.39%, hardly a bad run, just less good. All figures are annualised.

The gap is 5.50%

The FTSE's PE fell from 17.78 to 16.45, -.78% pa

The S&P's PE rose from 20.7 to 24.88 +1.86% pa

So 2.66% of the gap is explained by relative speculation or rerating, leaving 2.77% explained by additional earnings growth in the US. Both countries inflation rates and corporate profits/GDP ratios were comparable and during this period the US experienced a significant corporate tax cut. The 2000s had also been a worse decade for US earnings than the UK, so a reversion to the mean was to be expected.

I don't see a trend, I see volatility, opportunity and value.

I just think we're not doing so well here in the UK.

Over the pond they've created companies like Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Microsoft etc etc etc etc

In China Jack Ma had Alibaba and now has Ant, Richard Liu has JD.

Apple alone is worth the same as the whole FTSE100

OK we have AZN, GSK but nothing much of interest to invest in, just lots of dinosaurs in FTSE100

In the 250 and allshare it's a bit more interesting but we've created nothing scalable.

A real shame, but that's just how it is.

We had the biggest navy in the world once, and the pound was worth >$4.

Is this all part of a cycle that's going to reverse in the coming years? I think not. The main investment opportunities are now elsewhere, and that may not necessarily be in the US.

People were excited about rail right through the 1800s, then it was cars, aviation, radio, phones, the information age, anything with a .com in the name, and now a whole bunch of things all at once - tech, healthcare, consumer staples, cannabis, bitcoin, electric vehicles, renewables..."Technological change does notincrease profits unless firms have lasting monopolies, a condition that rarely occurs...

As Warren Buffet (1999) and Jeremy Siegel (1999, 2000) have pointed out, in a competitive economy technological change largely benefits consumers through a higher standard of living, rather than benefiting the owners of capital." (doi:10.1016/j.pacfin.2005.07.001)UK GDP and corporate earnings have been doing just fine compared with their US counterparts since the Millennium. America's main advantage at the moment is that not only is their own boomer generation flooding their economy with capital, ontop of incredible amounts of QE and fiscal stimulus, but they're also being flooded with cheap capital from the rest of the world. Temporarily that can create an illusion of higher growth, and I grant this situation is without a historical precedent I'm aware of, but it can't last. The UK's main problem pre-covid was why aren't we getting any real productivity growth or real median income growth since 2007? That is the main cause of real earnings growth in the long term.Very good points here. A lack of investment by corporations can result in low productivity growth. If you lower the bar for investment returns by lowering the risk free rate, you dis-incentivise productive investment. Likewise globalisation has led to a surplus of cheap labour which also dis-incentivise capital investments. Logically a return of inflation due to higher labour costs and resulting higher interest rates should force companies to adapt to the new regime and spend money to invest in productivity enhancing capital investments (or try at least).Always nice to be appreciated You sound like you've read The Great Demographic Reversal (I've ordered mine but it hasn't arrived yet).I think de-globalisation is already under way, companies are already looking at desourcing from Chinese dependence. From the UK perspective, when globally 1960s Boomer divestment and retirement really kicks in from ~2030 onwards, our 40% food imports will be safe as they're mostly EU and US; energy needs may be taken care of by domestic renewables/shale, direct EU imports, US shale and what's left in the North Sea; raw materials from re-using/recycling, and from trade routes that China can't touch (e.g. Australian Aluminium can get to the smelters in Iceland around the Cape of Good Hope or via the Panama Canal rather than the Suez route); and our infrastructure and human capital is fine.2

You sound like you've read The Great Demographic Reversal (I've ordered mine but it hasn't arrived yet).I think de-globalisation is already under way, companies are already looking at desourcing from Chinese dependence. From the UK perspective, when globally 1960s Boomer divestment and retirement really kicks in from ~2030 onwards, our 40% food imports will be safe as they're mostly EU and US; energy needs may be taken care of by domestic renewables/shale, direct EU imports, US shale and what's left in the North Sea; raw materials from re-using/recycling, and from trade routes that China can't touch (e.g. Australian Aluminium can get to the smelters in Iceland around the Cape of Good Hope or via the Panama Canal rather than the Suez route); and our infrastructure and human capital is fine.2 -

The global equity trackers mentioned to you here are suitable, as are many similar ones.nocash said:I want to punt £10k on the stock market as a 5-10 year investment. A friend suggested tracker fund. I will be researching the web over the next few days and only go with a well established firm. Are there any “go to” sites that will save time and provide reasonable range of options to review?

But there's a catch. You might be new to investing and newcomers have an unfortunate tendency to see big downward moves, get scared and take out their money with a big loss, then not invest again. Both covid and a US election are making stock markets more jittery than usual so conditions at the moment are quite likely to lead to some significant tests of your ability to handle the emotional reaction to losing money in the short term in stock markets that behave like a rollercoaster in reverse, with an upward trend but lots of bouncing around along the way.

So assuming you're a newcomer I suggest that you:

1. Invest £1,000 and check and track the price every day. This is to help you get a better feel for what markets do and how you react to those things. Much easier to deal with being £400 down with £9,000 in the bank than £4,000 down and an empty account. If you're really lucky you'll get some 20-40% over a week or three drops to test and train your reactions.

2. Leave the rest in savings until one of these things happens:

2a. it's more than 100 days from the next US Presidential inauguration and there is at east one effective covid vaccine in wide use in developing countries. Invest the remainder.

2b. if your investment drops to more than 20% below where it was a week ago. Invest another £4,000.

2c. if your investment drops to more than 40% below where it was a week ago. Invest the remainder.

Those conditions suggest acting when the known short term volatility sources may have abated or when prices have shifted far enough in your favour to be worth the extra challenge to your emotions.

1 -

@bowlhead99, @Another_Saver , thanks for the kind words. Do you have an thoughts beyond mine for our original poster on how they might manage the vicissitudes that face a new investor?

0 -

Buy right, hold tight, a good, cheap multi asset fund like HSBC global strategy balanced or VLS 60 will see you through just fine.jamesd said:@bowlhead99, @Another_Saver , thanks for the kind words. Do you have an thoughts beyond mine for our original poster on how they might manage the vicissitudes that face a new investor?

Whoever would have thought stating facts about capital markets would be so controversial, and just like in the other thread (https://forums.moneysavingexpert.com/discussion/6206301/vvfusi-or-vmid#latest)@bowlhead99 seems to have gone quiet once proved wrong.

0 -

Another_Saver said:itwasntme001 said:Another_Saver said:

For convenience let's use year end 2009 to year-end 2019. This is far too short a time period to infer anything from.Steve182 said:

Last decade the difference has been massively in favour of S & P 500TBC15 said:

So what's the relative performance over say 10yrs?Another_Saver said:

Rather that than the S&P 500 full of dot com valuation consumer electronics and media companies, and healthcare companies that won't be around when the US inevitably switches to public healthcare.TBC15 said:The FTSE 100 is a Jurassic index, to be avoided at all costs.

This is to 2018. You will find something more recent if you persevere on Google I'm sure. The trend has continued in the same direction since then, but that's no indication of what will happen next... The S&P returned 13.3%, the FTSE 100 7.39%, hardly a bad run, just less good. All figures are annualised.

The S&P returned 13.3%, the FTSE 100 7.39%, hardly a bad run, just less good. All figures are annualised.

The gap is 5.50%

The FTSE's PE fell from 17.78 to 16.45, -.78% pa

The S&P's PE rose from 20.7 to 24.88 +1.86% pa

So 2.66% of the gap is explained by relative speculation or rerating, leaving 2.77% explained by additional earnings growth in the US. Both countries inflation rates and corporate profits/GDP ratios were comparable and during this period the US experienced a significant corporate tax cut. The 2000s had also been a worse decade for US earnings than the UK, so a reversion to the mean was to be expected.

I don't see a trend, I see volatility, opportunity and value.

Edit: this isn't just the UK, the US has outperformed just about everything except bitcoin and Tesla in the last decade and year to date.This is a really good post and wish there was more of this sort of analysis on here. The US markets have benefited from monopolistic powers in tech (further exacerbated by their immense global reach) with an economic backdrop of disinflation (which has so far kept long term interest rates very low thereby boosting valuations).When we do get inflation returning, if it is in the context of reflationary economic conditions, a FTSE100 tracker should start to outperform the US markets.itwasntme001 said:Another_Saver said:

Everyone has always said that since the Acts of Union. Declinist nostalgic moaning isn't new, it's our oldest tradition. And the things you bemoan were only possible because of the empire (also known as stealing other peoples' countries for your own economic advantage), it's a structural change not an economic one.Steve182 said:

I disagree,Another_Saver said:

For convenience let's use year end 2009 to year-end 2019. This is far too short a time period to infer anything from.Steve182 said:

Last decade the difference has been massively in favour of S & P 500TBC15 said:

So what's the relative performance over say 10yrs?Another_Saver said:

Rather that than the S&P 500 full of dot com valuation consumer electronics and media companies, and healthcare companies that won't be around when the US inevitably switches to public healthcare.TBC15 said:The FTSE 100 is a Jurassic index, to be avoided at all costs.

This is to 2018. You will find something more recent if you persevere on Google I'm sure. The trend has continued in the same direction since then, but that's no indication of what will happen next... The S&P returned 13.3%, the FTSE 100 7.39%, hardly a bad run, just less good. All figures are annualised.

The S&P returned 13.3%, the FTSE 100 7.39%, hardly a bad run, just less good. All figures are annualised.

The gap is 5.50%

The FTSE's PE fell from 17.78 to 16.45, -.78% pa

The S&P's PE rose from 20.7 to 24.88 +1.86% pa

So 2.66% of the gap is explained by relative speculation or rerating, leaving 2.77% explained by additional earnings growth in the US. Both countries inflation rates and corporate profits/GDP ratios were comparable and during this period the US experienced a significant corporate tax cut. The 2000s had also been a worse decade for US earnings than the UK, so a reversion to the mean was to be expected.

I don't see a trend, I see volatility, opportunity and value.

I just think we're not doing so well here in the UK.

Over the pond they've created companies like Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Microsoft etc etc etc etc

In China Jack Ma had Alibaba and now has Ant, Richard Liu has JD.

Apple alone is worth the same as the whole FTSE100

OK we have AZN, GSK but nothing much of interest to invest in, just lots of dinosaurs in FTSE100

In the 250 and allshare it's a bit more interesting but we've created nothing scalable.

A real shame, but that's just how it is.

We had the biggest navy in the world once, and the pound was worth >$4.

Is this all part of a cycle that's going to reverse in the coming years? I think not. The main investment opportunities are now elsewhere, and that may not necessarily be in the US.

People were excited about rail right through the 1800s, then it was cars, aviation, radio, phones, the information age, anything with a .com in the name, and now a whole bunch of things all at once - tech, healthcare, consumer staples, cannabis, bitcoin, electric vehicles, renewables..."Technological change does notincrease profits unless firms have lasting monopolies, a condition that rarely occurs...

As Warren Buffet (1999) and Jeremy Siegel (1999, 2000) have pointed out, in a competitive economy technological change largely benefits consumers through a higher standard of living, rather than benefiting the owners of capital." (doi:10.1016/j.pacfin.2005.07.001)UK GDP and corporate earnings have been doing just fine compared with their US counterparts since the Millennium. America's main advantage at the moment is that not only is their own boomer generation flooding their economy with capital, ontop of incredible amounts of QE and fiscal stimulus, but they're also being flooded with cheap capital from the rest of the world. Temporarily that can create an illusion of higher growth, and I grant this situation is without a historical precedent I'm aware of, but it can't last. The UK's main problem pre-covid was why aren't we getting any real productivity growth or real median income growth since 2007? That is the main cause of real earnings growth in the long term.Very good points here. A lack of investment by corporations can result in low productivity growth. If you lower the bar for investment returns by lowering the risk free rate, you dis-incentivise productive investment. Likewise globalisation has led to a surplus of cheap labour which also dis-incentivise capital investments. Logically a return of inflation due to higher labour costs and resulting higher interest rates should force companies to adapt to the new regime and spend money to invest in productivity enhancing capital investments (or try at least).Always nice to be appreciated You sound like you've read The Great Demographic Reversal (I've ordered mine but it hasn't arrived yet).I think de-globalisation is already under way, companies are already looking at desourcing from Chinese dependence. From the UK perspective, when globally 1960s Boomer divestment and retirement really kicks in from ~2030 onwards, our 40% food imports will be safe as they're mostly EU and US; energy needs may be taken care of by domestic renewables/shale, direct EU imports, US shale and what's left in the North Sea; raw materials from re-using/recycling, and from trade routes that China can't touch (e.g. Australian Aluminium can get to the smelters in Iceland around the Cape of Good Hope or via the Panama Canal rather than the Suez route); and our infrastructure and human capital is fine.No haven't read yet, still have to order my copy. I did read the authors paper - I think BIS 656 - over a year ago. I have been an investment professional for a whilst so perhaps some of what I say is based on my experiences. Although I am in my 30s so a lot to learn still!Globalisation arguably peaked about 12 years ago now. It is incredibly difficult to forecast how and when all manner of things will play out. I did see somewhere that the authors have been forecasting for inflation of 5-10% within the next few years which would be obviously a game changer in terms of asset class performance (especially between sectors) because the economic regime would fundamentally change and market expectations would see a massive shift. I am a bit sceptical as I think they are downplaying the technology (in terms of AI and robotics) that provides a risk to their thesis. There are a lot of BS jobs in the western world that can be automated away, freeing up human capital to help in more social endeavours. This also means MMT can be more sustainable long term although of course MMT can also dis-incentivise people from working.So very interesting to read different opinions but there is a lot we do not know about the future and to downplay innovation (simply because the authors are not capable of understanding it) may very well be dangerous if you assume their thesis to be correct.1

You sound like you've read The Great Demographic Reversal (I've ordered mine but it hasn't arrived yet).I think de-globalisation is already under way, companies are already looking at desourcing from Chinese dependence. From the UK perspective, when globally 1960s Boomer divestment and retirement really kicks in from ~2030 onwards, our 40% food imports will be safe as they're mostly EU and US; energy needs may be taken care of by domestic renewables/shale, direct EU imports, US shale and what's left in the North Sea; raw materials from re-using/recycling, and from trade routes that China can't touch (e.g. Australian Aluminium can get to the smelters in Iceland around the Cape of Good Hope or via the Panama Canal rather than the Suez route); and our infrastructure and human capital is fine.No haven't read yet, still have to order my copy. I did read the authors paper - I think BIS 656 - over a year ago. I have been an investment professional for a whilst so perhaps some of what I say is based on my experiences. Although I am in my 30s so a lot to learn still!Globalisation arguably peaked about 12 years ago now. It is incredibly difficult to forecast how and when all manner of things will play out. I did see somewhere that the authors have been forecasting for inflation of 5-10% within the next few years which would be obviously a game changer in terms of asset class performance (especially between sectors) because the economic regime would fundamentally change and market expectations would see a massive shift. I am a bit sceptical as I think they are downplaying the technology (in terms of AI and robotics) that provides a risk to their thesis. There are a lot of BS jobs in the western world that can be automated away, freeing up human capital to help in more social endeavours. This also means MMT can be more sustainable long term although of course MMT can also dis-incentivise people from working.So very interesting to read different opinions but there is a lot we do not know about the future and to downplay innovation (simply because the authors are not capable of understanding it) may very well be dangerous if you assume their thesis to be correct.1 -

I did explain why I hadn't spent the time to reply to your four posts in a row on that other thread, although some of the content was picked up within this one, so no great loss other than your ego being a bit bruised from feeling you were being ignored over there.Another_Saver said:

and just like in the other thread (https://forums.moneysavingexpert.com/discussion/6206301/vvfusi-or-vmid#latest)@bowlhead99 seems to have gone quiet once proved wrong.

On this one, the fact I haven't kept up with your frenetic pace of posting 16 posts on a single beginner's thread within 24 hours shouldn't be taken as an inference that I've 'gone quiet' - simply that most people don't have time to keep up with your persistence to the cause. FWIW it doesn't seem that I've actually been 'proved wrong' about anything at all; each of my paragraphs are fine in their context.

HTH3 -

I'm an eternal sceptic, but I think Eric Brynjolfsson has a point when he compares the 4th Industrial Revolution with previous iterations while also saying it is different in the information age and that the information age economy is really just getting started. Goods are instantly replicable with 100% accuracy, everything is available for free or cheaply anywhere anytime, innovations beget innovations, tech giants create new economies of opportunity around their platforms, commuting is redundant, communication is instant and free and has no marginal scaling costs, many administrative level jobs are becoming human-optional, the upper limits on what is achievable are less clear cut whereas, to take ane "old" industry as an example, there is only so much oil in the world and only so much driving people need to do.itwasntme001 said:Another_Saver said:itwasntme001 said:Another_Saver said:

For convenience let's use year end 2009 to year-end 2019. This is far too short a time period to infer anything from.Steve182 said:

Last decade the difference has been massively in favour of S & P 500TBC15 said:

So what's the relative performance over say 10yrs?Another_Saver said:

Rather that than the S&P 500 full of dot com valuation consumer electronics and media companies, and healthcare companies that won't be around when the US inevitably switches to public healthcare.TBC15 said:The FTSE 100 is a Jurassic index, to be avoided at all costs.

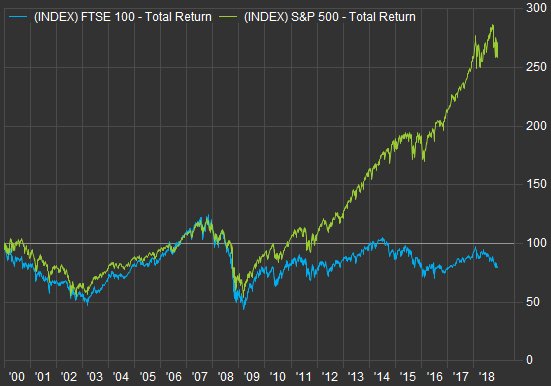

This is to 2018. You will find something more recent if you persevere on Google I'm sure. The trend has continued in the same direction since then, but that's no indication of what will happen next... The S&P returned 13.3%, the FTSE 100 7.39%, hardly a bad run, just less good. All figures are annualised.

The S&P returned 13.3%, the FTSE 100 7.39%, hardly a bad run, just less good. All figures are annualised.

The gap is 5.50%

The FTSE's PE fell from 17.78 to 16.45, -.78% pa

The S&P's PE rose from 20.7 to 24.88 +1.86% pa

So 2.66% of the gap is explained by relative speculation or rerating, leaving 2.77% explained by additional earnings growth in the US. Both countries inflation rates and corporate profits/GDP ratios were comparable and during this period the US experienced a significant corporate tax cut. The 2000s had also been a worse decade for US earnings than the UK, so a reversion to the mean was to be expected.

I don't see a trend, I see volatility, opportunity and value.

Edit: this isn't just the UK, the US has outperformed just about everything except bitcoin and Tesla in the last decade and year to date.This is a really good post and wish there was more of this sort of analysis on here. The US markets have benefited from monopolistic powers in tech (further exacerbated by their immense global reach) with an economic backdrop of disinflation (which has so far kept long term interest rates very low thereby boosting valuations).When we do get inflation returning, if it is in the context of reflationary economic conditions, a FTSE100 tracker should start to outperform the US markets.itwasntme001 said:Another_Saver said:

Everyone has always said that since the Acts of Union. Declinist nostalgic moaning isn't new, it's our oldest tradition. And the things you bemoan were only possible because of the empire (also known as stealing other peoples' countries for your own economic advantage), it's a structural change not an economic one.Steve182 said:

I disagree,Another_Saver said:

For convenience let's use year end 2009 to year-end 2019. This is far too short a time period to infer anything from.Steve182 said:

Last decade the difference has been massively in favour of S & P 500TBC15 said:

So what's the relative performance over say 10yrs?Another_Saver said:

Rather that than the S&P 500 full of dot com valuation consumer electronics and media companies, and healthcare companies that won't be around when the US inevitably switches to public healthcare.TBC15 said:The FTSE 100 is a Jurassic index, to be avoided at all costs.

This is to 2018. You will find something more recent if you persevere on Google I'm sure. The trend has continued in the same direction since then, but that's no indication of what will happen next... The S&P returned 13.3%, the FTSE 100 7.39%, hardly a bad run, just less good. All figures are annualised.

The S&P returned 13.3%, the FTSE 100 7.39%, hardly a bad run, just less good. All figures are annualised.

The gap is 5.50%

The FTSE's PE fell from 17.78 to 16.45, -.78% pa

The S&P's PE rose from 20.7 to 24.88 +1.86% pa

So 2.66% of the gap is explained by relative speculation or rerating, leaving 2.77% explained by additional earnings growth in the US. Both countries inflation rates and corporate profits/GDP ratios were comparable and during this period the US experienced a significant corporate tax cut. The 2000s had also been a worse decade for US earnings than the UK, so a reversion to the mean was to be expected.

I don't see a trend, I see volatility, opportunity and value.

I just think we're not doing so well here in the UK.

Over the pond they've created companies like Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Microsoft etc etc etc etc

In China Jack Ma had Alibaba and now has Ant, Richard Liu has JD.

Apple alone is worth the same as the whole FTSE100

OK we have AZN, GSK but nothing much of interest to invest in, just lots of dinosaurs in FTSE100

In the 250 and allshare it's a bit more interesting but we've created nothing scalable.

A real shame, but that's just how it is.

We had the biggest navy in the world once, and the pound was worth >$4.

Is this all part of a cycle that's going to reverse in the coming years? I think not. The main investment opportunities are now elsewhere, and that may not necessarily be in the US.

People were excited about rail right through the 1800s, then it was cars, aviation, radio, phones, the information age, anything with a .com in the name, and now a whole bunch of things all at once - tech, healthcare, consumer staples, cannabis, bitcoin, electric vehicles, renewables..."Technological change does notincrease profits unless firms have lasting monopolies, a condition that rarely occurs...

As Warren Buffet (1999) and Jeremy Siegel (1999, 2000) have pointed out, in a competitive economy technological change largely benefits consumers through a higher standard of living, rather than benefiting the owners of capital." (doi:10.1016/j.pacfin.2005.07.001)UK GDP and corporate earnings have been doing just fine compared with their US counterparts since the Millennium. America's main advantage at the moment is that not only is their own boomer generation flooding their economy with capital, ontop of incredible amounts of QE and fiscal stimulus, but they're also being flooded with cheap capital from the rest of the world. Temporarily that can create an illusion of higher growth, and I grant this situation is without a historical precedent I'm aware of, but it can't last. The UK's main problem pre-covid was why aren't we getting any real productivity growth or real median income growth since 2007? That is the main cause of real earnings growth in the long term.Very good points here. A lack of investment by corporations can result in low productivity growth. If you lower the bar for investment returns by lowering the risk free rate, you dis-incentivise productive investment. Likewise globalisation has led to a surplus of cheap labour which also dis-incentivise capital investments. Logically a return of inflation due to higher labour costs and resulting higher interest rates should force companies to adapt to the new regime and spend money to invest in productivity enhancing capital investments (or try at least).Always nice to be appreciated You sound like you've read The Great Demographic Reversal (I've ordered mine but it hasn't arrived yet).I think de-globalisation is already under way, companies are already looking at desourcing from Chinese dependence. From the UK perspective, when globally 1960s Boomer divestment and retirement really kicks in from ~2030 onwards, our 40% food imports will be safe as they're mostly EU and US; energy needs may be taken care of by domestic renewables/shale, direct EU imports, US shale and what's left in the North Sea; raw materials from re-using/recycling, and from trade routes that China can't touch (e.g. Australian Aluminium can get to the smelters in Iceland around the Cape of Good Hope or via the Panama Canal rather than the Suez route); and our infrastructure and human capital is fine.No haven't read yet, still have to order my copy. I did read the authors paper - I think BIS 656 - over a year ago. I have been an investment professional for a whilst so perhaps some of what I say is based on my experiences. Although I am in my 30s so a lot to learn still!Globalisation arguably peaked about 12 years ago now. It is incredibly difficult to forecast how and when all manner of things will play out. I did see somewhere that the authors have been forecasting for inflation of 5-10% within the next few years which would be obviously a game changer in terms of asset class performance (especially between sectors) because the economic regime would fundamentally change and market expectations would see a massive shift. I am a bit sceptical as I think they are downplaying the technology (in terms of AI and robotics) that provides a risk to their thesis. There are a lot of BS jobs in the western world that can be automated away, freeing up human capital to help in more social endeavours. This also means MMT can be more sustainable long term although of course MMT can also dis-incentivise people from working.So very interesting to read different opinions but there is a lot we do not know about the future and to downplay innovation (simply because the authors are not capable of understanding it) may very well be dangerous if you assume their thesis to be correct.But if we accept Buffett, Ritter and Siegel's (references in my previous posts) statements about technology benefitting consumers more than capital owners through raised living standards, then maybe an index like the UK that lacks tech will benefit indirectly from technological evolutions to come more than the S&P 500 with its 40% tech weighting.Edit: another caveat to my point about GDP/equity returns is, as Brynjolfsson suggests, conventional econometrics isn't good at measuring "new economy" growth. Interesting time, eh...Anyway - for most people a good, cheap global equity index fund is a sound investment, or a global multi-asset fund to keep the risk down.

You sound like you've read The Great Demographic Reversal (I've ordered mine but it hasn't arrived yet).I think de-globalisation is already under way, companies are already looking at desourcing from Chinese dependence. From the UK perspective, when globally 1960s Boomer divestment and retirement really kicks in from ~2030 onwards, our 40% food imports will be safe as they're mostly EU and US; energy needs may be taken care of by domestic renewables/shale, direct EU imports, US shale and what's left in the North Sea; raw materials from re-using/recycling, and from trade routes that China can't touch (e.g. Australian Aluminium can get to the smelters in Iceland around the Cape of Good Hope or via the Panama Canal rather than the Suez route); and our infrastructure and human capital is fine.No haven't read yet, still have to order my copy. I did read the authors paper - I think BIS 656 - over a year ago. I have been an investment professional for a whilst so perhaps some of what I say is based on my experiences. Although I am in my 30s so a lot to learn still!Globalisation arguably peaked about 12 years ago now. It is incredibly difficult to forecast how and when all manner of things will play out. I did see somewhere that the authors have been forecasting for inflation of 5-10% within the next few years which would be obviously a game changer in terms of asset class performance (especially between sectors) because the economic regime would fundamentally change and market expectations would see a massive shift. I am a bit sceptical as I think they are downplaying the technology (in terms of AI and robotics) that provides a risk to their thesis. There are a lot of BS jobs in the western world that can be automated away, freeing up human capital to help in more social endeavours. This also means MMT can be more sustainable long term although of course MMT can also dis-incentivise people from working.So very interesting to read different opinions but there is a lot we do not know about the future and to downplay innovation (simply because the authors are not capable of understanding it) may very well be dangerous if you assume their thesis to be correct.But if we accept Buffett, Ritter and Siegel's (references in my previous posts) statements about technology benefitting consumers more than capital owners through raised living standards, then maybe an index like the UK that lacks tech will benefit indirectly from technological evolutions to come more than the S&P 500 with its 40% tech weighting.Edit: another caveat to my point about GDP/equity returns is, as Brynjolfsson suggests, conventional econometrics isn't good at measuring "new economy" growth. Interesting time, eh...Anyway - for most people a good, cheap global equity index fund is a sound investment, or a global multi-asset fund to keep the risk down.

2 -

bowlhead99 said:

I did explain why I hadn't spent the time to reply to your four posts in a row on that other thread, although some of the content was picked up within this one, so no great loss other than your ego being a bit bruised from feeling you were being ignored over there.Another_Saver said:

and just like in the other thread (https://forums.moneysavingexpert.com/discussion/6206301/vvfusi-or-vmid#latest)@bowlhead99 seems to have gone quiet once proved wrong.

On this one, the fact I haven't kept up with your frenetic pace of posting 16 posts on a single beginner's thread within 24 hours shouldn't be taken as an inference that I've 'gone quiet' - simply that most people don't have time to keep up with your persistence to the cause. FWIW it doesn't seem that I've actually been 'proved wrong' about anything at all; each of my paragraphs are fine in their context.

HTHDo you have something to add?@bowlhead99 contends on various threads that companies issuing shares essentially does not affect existing shareholders (on aggregate). Perhaps the Investopedia page on share dilution would be useful (https://www.investopedia.com/articles/stocks/11/dangers-of-stock-dilution.asp).@bowlhead99's argument seems to be that, as there is no direct loss or cost to existing shareholders, and since it is a means of raising capital to generate earnings, dilution within an index such as the FTSE 100 should not be thought of as causing the aggregate shareholder's returns per share to lag the aggregate returns by the extent of dilution, explaining the point by analogy and hypothetical scenarios. Does anyone else has a simpler way of explaining this?I have yet to see @bowlhead99 refer to any source - a textbook, an article, something, anything - and I would greatly appreciate if they would either admit they are wrong or provide a cogent and credible explanation as to why they are right. I have already listed the numerous caveats that apply to my point, including globalisation. Having to correct someone who presents themselves as a heavyweight but can't understand the basic dynamics of capital markets is tiring frankly, but since I'm here and invested in this forum now, I feel obliged to.And yes, I have noticed your arguments keep changing slightly from post to post - you don't have to do that when you know you're right.1 -

Another_Saver said:

I'm an eternal sceptic, but I think Eric Brynjolfsson has a point when he compares the 4th Industrial Revolution with previous iterations while also saying it is different in the information age and that the information age economy is really just getting started. Goods are instantly replicable with 100% accuracy, everything is available for free or cheaply anywhere anytime, innovations beget innovations, tech giants create new economies of opportunity around their platforms, commuting is redundant, communication is instant and free and has no marginal scaling costs, many administrative level jobs are becoming human-optional, the upper limits on what is achievable are less clear cut whereas, to take ane "old" industry as an example, there is only so much oil in the world and only so much driving people need to do.itwasntme001 said:Another_Saver said:itwasntme001 said:Another_Saver said:

For convenience let's use year end 2009 to year-end 2019. This is far too short a time period to infer anything from.Steve182 said:

Last decade the difference has been massively in favour of S & P 500TBC15 said:

So what's the relative performance over say 10yrs?Another_Saver said:

Rather that than the S&P 500 full of dot com valuation consumer electronics and media companies, and healthcare companies that won't be around when the US inevitably switches to public healthcare.TBC15 said:The FTSE 100 is a Jurassic index, to be avoided at all costs.

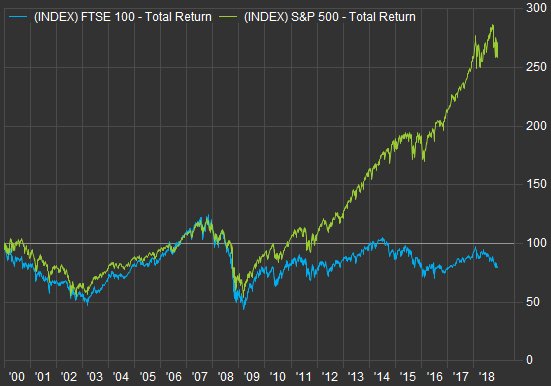

This is to 2018. You will find something more recent if you persevere on Google I'm sure. The trend has continued in the same direction since then, but that's no indication of what will happen next... The S&P returned 13.3%, the FTSE 100 7.39%, hardly a bad run, just less good. All figures are annualised.

The S&P returned 13.3%, the FTSE 100 7.39%, hardly a bad run, just less good. All figures are annualised.

The gap is 5.50%

The FTSE's PE fell from 17.78 to 16.45, -.78% pa

The S&P's PE rose from 20.7 to 24.88 +1.86% pa

So 2.66% of the gap is explained by relative speculation or rerating, leaving 2.77% explained by additional earnings growth in the US. Both countries inflation rates and corporate profits/GDP ratios were comparable and during this period the US experienced a significant corporate tax cut. The 2000s had also been a worse decade for US earnings than the UK, so a reversion to the mean was to be expected.

I don't see a trend, I see volatility, opportunity and value.

Edit: this isn't just the UK, the US has outperformed just about everything except bitcoin and Tesla in the last decade and year to date.This is a really good post and wish there was more of this sort of analysis on here. The US markets have benefited from monopolistic powers in tech (further exacerbated by their immense global reach) with an economic backdrop of disinflation (which has so far kept long term interest rates very low thereby boosting valuations).When we do get inflation returning, if it is in the context of reflationary economic conditions, a FTSE100 tracker should start to outperform the US markets.itwasntme001 said:Another_Saver said:

Everyone has always said that since the Acts of Union. Declinist nostalgic moaning isn't new, it's our oldest tradition. And the things you bemoan were only possible because of the empire (also known as stealing other peoples' countries for your own economic advantage), it's a structural change not an economic one.Steve182 said:

I disagree,Another_Saver said:

For convenience let's use year end 2009 to year-end 2019. This is far too short a time period to infer anything from.Steve182 said:

Last decade the difference has been massively in favour of S & P 500TBC15 said:

So what's the relative performance over say 10yrs?Another_Saver said:

Rather that than the S&P 500 full of dot com valuation consumer electronics and media companies, and healthcare companies that won't be around when the US inevitably switches to public healthcare.TBC15 said:The FTSE 100 is a Jurassic index, to be avoided at all costs.

This is to 2018. You will find something more recent if you persevere on Google I'm sure. The trend has continued in the same direction since then, but that's no indication of what will happen next... The S&P returned 13.3%, the FTSE 100 7.39%, hardly a bad run, just less good. All figures are annualised.

The S&P returned 13.3%, the FTSE 100 7.39%, hardly a bad run, just less good. All figures are annualised.

The gap is 5.50%

The FTSE's PE fell from 17.78 to 16.45, -.78% pa

The S&P's PE rose from 20.7 to 24.88 +1.86% pa

So 2.66% of the gap is explained by relative speculation or rerating, leaving 2.77% explained by additional earnings growth in the US. Both countries inflation rates and corporate profits/GDP ratios were comparable and during this period the US experienced a significant corporate tax cut. The 2000s had also been a worse decade for US earnings than the UK, so a reversion to the mean was to be expected.

I don't see a trend, I see volatility, opportunity and value.

I just think we're not doing so well here in the UK.

Over the pond they've created companies like Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Microsoft etc etc etc etc

In China Jack Ma had Alibaba and now has Ant, Richard Liu has JD.

Apple alone is worth the same as the whole FTSE100

OK we have AZN, GSK but nothing much of interest to invest in, just lots of dinosaurs in FTSE100

In the 250 and allshare it's a bit more interesting but we've created nothing scalable.

A real shame, but that's just how it is.

We had the biggest navy in the world once, and the pound was worth >$4.

Is this all part of a cycle that's going to reverse in the coming years? I think not. The main investment opportunities are now elsewhere, and that may not necessarily be in the US.

People were excited about rail right through the 1800s, then it was cars, aviation, radio, phones, the information age, anything with a .com in the name, and now a whole bunch of things all at once - tech, healthcare, consumer staples, cannabis, bitcoin, electric vehicles, renewables..."Technological change does notincrease profits unless firms have lasting monopolies, a condition that rarely occurs...

As Warren Buffet (1999) and Jeremy Siegel (1999, 2000) have pointed out, in a competitive economy technological change largely benefits consumers through a higher standard of living, rather than benefiting the owners of capital." (doi:10.1016/j.pacfin.2005.07.001)UK GDP and corporate earnings have been doing just fine compared with their US counterparts since the Millennium. America's main advantage at the moment is that not only is their own boomer generation flooding their economy with capital, ontop of incredible amounts of QE and fiscal stimulus, but they're also being flooded with cheap capital from the rest of the world. Temporarily that can create an illusion of higher growth, and I grant this situation is without a historical precedent I'm aware of, but it can't last. The UK's main problem pre-covid was why aren't we getting any real productivity growth or real median income growth since 2007? That is the main cause of real earnings growth in the long term.Very good points here. A lack of investment by corporations can result in low productivity growth. If you lower the bar for investment returns by lowering the risk free rate, you dis-incentivise productive investment. Likewise globalisation has led to a surplus of cheap labour which also dis-incentivise capital investments. Logically a return of inflation due to higher labour costs and resulting higher interest rates should force companies to adapt to the new regime and spend money to invest in productivity enhancing capital investments (or try at least).Always nice to be appreciated You sound like you've read The Great Demographic Reversal (I've ordered mine but it hasn't arrived yet).I think de-globalisation is already under way, companies are already looking at desourcing from Chinese dependence. From the UK perspective, when globally 1960s Boomer divestment and retirement really kicks in from ~2030 onwards, our 40% food imports will be safe as they're mostly EU and US; energy needs may be taken care of by domestic renewables/shale, direct EU imports, US shale and what's left in the North Sea; raw materials from re-using/recycling, and from trade routes that China can't touch (e.g. Australian Aluminium can get to the smelters in Iceland around the Cape of Good Hope or via the Panama Canal rather than the Suez route); and our infrastructure and human capital is fine.No haven't read yet, still have to order my copy. I did read the authors paper - I think BIS 656 - over a year ago. I have been an investment professional for a whilst so perhaps some of what I say is based on my experiences. Although I am in my 30s so a lot to learn still!Globalisation arguably peaked about 12 years ago now. It is incredibly difficult to forecast how and when all manner of things will play out. I did see somewhere that the authors have been forecasting for inflation of 5-10% within the next few years which would be obviously a game changer in terms of asset class performance (especially between sectors) because the economic regime would fundamentally change and market expectations would see a massive shift. I am a bit sceptical as I think they are downplaying the technology (in terms of AI and robotics) that provides a risk to their thesis. There are a lot of BS jobs in the western world that can be automated away, freeing up human capital to help in more social endeavours. This also means MMT can be more sustainable long term although of course MMT can also dis-incentivise people from working.So very interesting to read different opinions but there is a lot we do not know about the future and to downplay innovation (simply because the authors are not capable of understanding it) may very well be dangerous if you assume their thesis to be correct.

You sound like you've read The Great Demographic Reversal (I've ordered mine but it hasn't arrived yet).I think de-globalisation is already under way, companies are already looking at desourcing from Chinese dependence. From the UK perspective, when globally 1960s Boomer divestment and retirement really kicks in from ~2030 onwards, our 40% food imports will be safe as they're mostly EU and US; energy needs may be taken care of by domestic renewables/shale, direct EU imports, US shale and what's left in the North Sea; raw materials from re-using/recycling, and from trade routes that China can't touch (e.g. Australian Aluminium can get to the smelters in Iceland around the Cape of Good Hope or via the Panama Canal rather than the Suez route); and our infrastructure and human capital is fine.No haven't read yet, still have to order my copy. I did read the authors paper - I think BIS 656 - over a year ago. I have been an investment professional for a whilst so perhaps some of what I say is based on my experiences. Although I am in my 30s so a lot to learn still!Globalisation arguably peaked about 12 years ago now. It is incredibly difficult to forecast how and when all manner of things will play out. I did see somewhere that the authors have been forecasting for inflation of 5-10% within the next few years which would be obviously a game changer in terms of asset class performance (especially between sectors) because the economic regime would fundamentally change and market expectations would see a massive shift. I am a bit sceptical as I think they are downplaying the technology (in terms of AI and robotics) that provides a risk to their thesis. There are a lot of BS jobs in the western world that can be automated away, freeing up human capital to help in more social endeavours. This also means MMT can be more sustainable long term although of course MMT can also dis-incentivise people from working.So very interesting to read different opinions but there is a lot we do not know about the future and to downplay innovation (simply because the authors are not capable of understanding it) may very well be dangerous if you assume their thesis to be correct.

But if we accept Buffett, Ritter and Siegel's (references in my previous posts) statements about technology benefitting consumers more than capital owners through raised living standards, then maybe an index like the UK that lacks tech will benefit indirectly from technological evolutions to come more than the S&P 500 with its 40% tech weighting.

Anyway - for most people a good, cheap global equity index fund is a sound investment, or a global multi-asset fund to keep the risk down.Yes agree that a cheap global index tracker is sound as long as its for the long term and within risk tolerance etc. One should probably expect close to 0% real returns for the next 10 years at current levels, but likely should do well in 20 years or so.There is a point where tech has priced in everything and then some and the old economy stocks, such as those in the FTSE100, start to do well or at least outperform the S&P. With oil, there is no way renewables will be used for trade tankers and trade lorries, at least for a long whilst yet and so diesel will still be used and will correlate quite well with global GDP and thus oil should see an upturn when the cycle turns back up.1 -

I do know what share dilution is thanks. Clearly a company issuing shares to new investors, or more shares to certain existing investors, dilutes existing owners of the shares who will now own a smaller piece of the pie when it comes to divvying up the profits. I don't know where I've ‘contended on various threads’ that this is not the case.Another_Saver said:bowlhead99 said:

I did explain why I hadn't spent the time to reply to your four posts in a row on that other thread, although some of the content was picked up within this one, so no great loss other than your ego being a bit bruised from feeling you were being ignored over there.Another_Saver said:

and just like in the other thread (https://forums.moneysavingexpert.com/discussion/6206301/vvfusi-or-vmid#latest)@bowlhead99 seems to have gone quiet once proved wrong.

On this one, the fact I haven't kept up with your frenetic pace of posting 16 posts on a single beginner's thread within 24 hours shouldn't be taken as an inference that I've 'gone quiet' - simply that most people don't have time to keep up with your persistence to the cause. FWIW it doesn't seem that I've actually been 'proved wrong' about anything at all; each of my paragraphs are fine in their context.

HTHDo you have something to add?bowlhead99 contends on various threads that companies issuing shares essentially does not affect existing shareholders (on aggregate). Perhaps the Investopedia page on share dilution would be useful (https://www.investopedia.com/articles/stocks/11/dangers-of-stock-dilution.asp).

Of course, most companies don't do this just for fun, because investors would be unhappy and not sanction it. The reasons for dilution are often positive - for example to fund investment and expansion, which enhances or maintains total earnings for each investor, because the overall profits rise. Or the company is raising money because it needs capital to stave off failure or regulatory sanction, so it is better to do it than not do it, as in its absence the profits per share would fall and the company could fail, while after the dilution they fall less far (so less loss per share) and the company doesn't fail. Whether the fundraise event is long-term accretive for existing shareholders depends on the circumstances, but when looking at it in the context of individual companies (rather than an index of companies) we can generally presume shareholders would prefer not to let too much of it happen if it was going to be too bad for their interests.bowlhead99's argument seems to be that, as there is no direct loss or cost to existing shareholders, and since it is a means of raising capital to generate earnings, dilution within an index such as the FTSE 100 should not be thought of as causing the aggregate shareholder's returns per share to lag the aggregate returns by the extent of dilution, explaining the point by analogy and hypothetical scenarios. Does anyone else has a simpler way of explaining this?If the FTSE100 companies valued at £1500bn between them were going to make £100bn profits between them and a new IPO rocks up - Maverick Industries - whose value is £30bn higher than the company it displaces and prospective profits are £2bn higher than the company it displaces, it will take a seat at the FTSE table and the total value of the FTSE100 companies will go up to £1530bn and total profits will go up to £102bn. The FTSE index figure of say 10,000 is unchanged by this event.Investors will adjust their holdings as necessary, perhaps acquiring shares in newco by swapping out some of their shares in oldcos. Overall, the enlarged investor community (or perhaps the same exact investors but more capital at risk per person, depending who funded the IPO) will have access to the £102bn profits that will be made, which supports the £1530bn valuation of the collective. It is true that the ownership by the ‘old money’ – the profits share represented by the pile of old share certificates – has been diluted down to be only 1500/1530ths of the total and will only get 100/102ths of the profit, but that is not necessarily an issue per se, because they are still getting the 100 they were going to get previously.Assuming P/E ratios stay the same: if all the companies in the new index are successful the next year they may each grow their profits by 10%, causing them to all be valued at a new value of 1530+153= 1683. The index would rise by 10% from its previous value when the market cap was 1530 (to be 11000 instead of 10000), but in total the market cap would have risen from 1500 to 1683 which is 12.2%. So as an observer you would say there has been some ‘dilution’ because you can see the market cap growth is more than the index growth, but everyone has still made the same return they would have made in the absence of the new entrant.The aggregate ‘returns per share’ of 10% is still just as good as the aggregate growth made by the constituents together (10% profits growth and 10% growth in valuation of each of the companies). All the new and old capital has made the same returns. The amount of capital being monitored in the index has gone up by a greater percentage than that, because new money came in from the outside (from investors bank accounts, or from the sale of other asset classes such as bonds or private equity holdings etc, or from a Russian oligarch), but it didn’t make investors worse off. Of course the old investors didn't take all the old and new profits, only the old proportion of the total profits, but they would have been welcome to use their own resources to buy in to the IPO for a greater proportion of the total pie if they had wanted their capital to make that extra return rather than someone else's capital to make that extra return.Alternatively, perhaps the new entrant is really successful because his efficient new international operation flying rubber dogs out of Hong Kong grows its profits by 20% while all the other companies only grew 10%. If that is recognised in company valuations the total value of the companies in aggregate would now be (30+6+1500+150=1686 instead of 30+3+1500+150). The 1686 represents a 10.2% increase in the 1530 from the start of the year, so the index goes up from 10000 to 11020 instead of 11000. The extra 0.2% growth came from the fact that 2% of the index delivered an extra 10% growth than the rest of the index.In that scenario of course we still end up with the market cap growing faster than the index (1686 from 1500 is 12.4% market cap growth compared to 10.2% performance index growth) so there was still evidently ‘dilution’ if the old investor set chooses not to introduce more capital and participate in the IPO fundraise themselves, but the index investors (who take a proportionate interest in all companies in the index) will make 10.2% profits, which is more profit than they would have made sans dilution.The performance increase they experienced came from admitting the new profitable FTSE100 constituent, but the same effect would have been felt if we were talking about one of the existing FTSE100 companies doing a capital fundraising to issue new shares to fund the lucrative airfreight business which delivered the extra annual profit.I assume your objection to my saying ‘this is not an issue’ is that your base assumption was that an index can’t grow faster than GDP and so any profits that could be made by the index of companies would be constrained by the fact that there’s only so much profit to go around... so if the ‘old investors’ have their percentage ownership of the index diluted by more capital (marketcap goes up faster than performance), they are destined to make less money than they were going to. However if the new company does not ‘steal profits’ from the existing companies, it is not really a closed system and the total amount of company valuation or annual profits represented by an index can and does freely float as a ratio to GDP for decades. It's obvious that if you allow someone else's capital to participate alongside yours in a market you will not personally make all the profits in the index, but you can still make the same percentage return on your money as you were going to, as long as the total profits made by the index can rise.For example, the revenues or profits to be made by Unilever are not limited to UK GDP growth but by the size of the South Asian or West African appetite for branded consumer products which can grow at a much higher rate. If investors in an index are ‘diluted’ by issuing shares of growth companies such as Ocado or Amazon or Boohoo or Morningstar Inc, they will get exposure to the profits from those companies, but they will not necessarily lose their existing profits to make way for it, because the revenues made by those expanding companies are revenues that were formerly made by BHS or Ikea or John Lewis or Matalan or FE Fundinfo who were not in the index anyway because of being private companies.I have already listed the numerous caveats that apply to my point, including globalisation.Basically you have a neat formula to ‘prove’ the make up of a valuation or market cap figure which only works if a whole load of assumptions hold true which in the real world will pretty often not hold true.

If I dare to mention why the assumptions you rely on for your model calculation may be flawed or not hold true, you would take it as an affront to your diligence, but you are happy to say yourself that everything needs to be caveated up the wazoo.

From your perspective, your model is spot on, though you acknowledged that it was only spot on to the extent of caveats for factors that can’t be easily predicted or quantified, so you don’t really know to what extent it is spot on; as you mention, academics have noted there are “numerous factors that can pull returns away from GDP over an investing lifetime” and that you, “have also explained that all the other factors that affect the market can cancel out capital dilution over an investing lifetime”, and that corporate profits can grow or shrink relative to GDP over long periods with the only boundary being that such periods must be “finite” rather than infinite, and a variety of other caveats you mentioned.

And yes, I have noticed your arguments keep changing slightly from post to post - you don't have to do that when you know you're right.-It would be quite boring if every thread used the same exact text to explain a point and two commenters just repeated their last posts verbatim until one got bored. So forgive me if I sometimes use different words to explain the point of view, which is not the same as 'changes his argument'; merely wondering which words may help it to 'click' with its reader.

2

Confirm your email address to Create Threads and Reply

Categories

- All Categories

- 353.5K Banking & Borrowing

- 254.1K Reduce Debt & Boost Income

- 455K Spending & Discounts

- 246.6K Work, Benefits & Business

- 602.9K Mortgages, Homes & Bills

- 178.1K Life & Family

- 260.6K Travel & Transport

- 1.5M Hobbies & Leisure

- 16K Discuss & Feedback

- 37.7K Read-Only Boards